The following is a response to Scott Alexander’s post about Rootclaim’s debate on the origins of Covid-19.

Prelude

We were initially excited to have Scott cover the story, hoping that someone with an affinity to probabilities would like to dig into our analysis and fully understand it. Sadly, Scott seemingly hadn’t enough time to do so and our exchange focused on fixing factual mistakes in earlier drafts of his post and explaining why rules-of-thumb in probabilistic thinking that he proposed do not work in practice. We did not get to discuss the details of our analysis, resulting in a post that is essentially a repeat of the judges’ reports with extra steps.

His post has two main messages:

- It’s hard to get probabilistic inference right – we fully agree with this and ironically his post is a great example, containing many probabilistic inference mistakes, some of which are listed below. While we agree it’s hard, our experience taught us that it is far from impossible.

- Zoonosis is a more likely hypothesis due to being better supported by the evidence – This is completely untrue, but to fully understand it one has to commit to learning how to do probabilistic inference correctly, which Scott could not free enough time to do.

Instead of explaining the whole methodology and how it applies to Covid origins, which will take too long, we will focus on the main mistake in all the analyses in Scott’s post – believing that the early cluster of cases in the Huanan Seafood Market (HSM) is strong evidence for zoonosis. Scott prepared a very useful table comparing the probabilities various people gave to the evidence about Covid origins (discussed later in more details). It nicely shows how the zoonosis conclusion stands on this single leg, and once it is removed, lab-leak becomes the winning hypothesis (Specifically, Scott will flip to 94% lab-leak).

Having explained this many times in many ways, we realize by now that it is not easy to understand, but we promise that those who make the effort will be rewarded with a glimpse of how much better we can all be at reasoning about the world, and will be able to reach high confidence that Covid originated from a lab.

Given this point’s importance, we will explain why HSM is negligible as evidence in three levels of detail: a simple version, a summarized version and a detailed version.

Simple version

- The zoonosis hypothesis fully depends on the claim that it is an extreme coincidence that the early Covid patients were in HSM – a market with wildlife – unless a zoonotic spillover occurred there.

- The rest of the evidence strongly supports the lab-leak hypothesis, so if this claim is mistaken, lab-leak becomes the most likely hypothesis.

- There are multiple cases where a country has had zero Covid cases for a while, and then a cluster of cases appears in a seafood market. In all these outbreaks, there is no contention that the source is not zoonotic, as it is genetically descended from the Wuhan outbreak.

- Since zero Covid periods are fairly rare, it is impossible to have so many market outbreaks unless there is something special about these locations. We discuss below what that may be, but whatever it is, it likely also applies to HSM, which is the largest seafood market in central China.

- This collapses the ‘extreme coincidence’ claim, which as explained above, turns lab-leak into the leading hypothesis.

Summarized version

- There is no contention that the strength of evidence is measured by the ratio of the conditional probabilities of that evidence under the different hypotheses – how likely are we to encounter such evidence assuming a certain hypothesis is true (Known as the Bayes factor or likelihood ratio).

- We will examine the conditional probability of an HSM early cluster given that we already know a pandemic has started in Wuhan. In shorthand, we are comparing

p(HSM|Zoonosis,Wuhan) to p(HSM|Lab Leak,Wuhan). - p(HSM|Lab Leak,Wuhan) – The mistake everyone makes here is thinking this is a 0.1% to 0.01% coincidence, usually justified by the first officially confirmed case being an HSM shrimp vendor, one of 1000 HSM vendors, out of 10 million Wuhan residents.

- We use three independent methods to estimate this probability more accurately, all pointing to this number being larger than 1%. As this is the short version, here is the simplest way to see it: HSM is not such a coincidence since seafood markets and facilities repeatedly form early clusters.

- 2 out of 5 large outbreaks in China in 2020, as well as outbreaks in Thailand and Singapore, started in markets.

- Most notable among them is the December 2020 outbreak in Thailand, following a long period of zero Covid (i.e. forming an early cluster just like HSM). That too happened in a seafood market, and the index case there was also a shrimp vendor!

Given that there are not that many early clusters after zero Covid (different from just any superspreader event!), having one so similar is enough to understand HSM is not some random location that can be evaluated with a naive division of population numbers.

- p(HSM|Zoonosis,Wuhan) – On the other hand, markets are not such a likely location for zoonotic spillovers. The “we told you so” statements about markets are mostly hindsight bias. When examining data prior to 2020 (more below), we see that scientists warned of interfaces where people dealt much more closely with animals, such as in farms, restaurants and labs. And indeed, in the first SARS epidemic, spillovers mostly occurred in restaurants.

So, given that markets are just one of many possible spillover locations, and HSM was not the only market with wildlife in Wuhan, we calculate (below) a conditional probability of 3-5%. - At this point, what was claimed to be 10,000x evidence (increases the odds of the zoonosis hypothesis by 10,000), turns out to be less than 5x – Because, as explained in 1, we need to divide the two conditional probabilities, which are at best 5% and 1%, giving a ratio lower than 5x.

- Last, the remarkable lack of evidence for a wildlife spillover in HSM, despite an extensive search, further reduces this factor.

- The HSM early cluster is therefore negligible as evidence. Our analysis assigns it 2x.

Long Version

This section will expand on the important points above, providing more evidence to support them, and a deeper understanding of why this is the best way to approach this question.

How to quantify probabilities – Why all hypotheses must be steelmanned

The text below is copied from one of our previous blog posts.

The mistake of assigning extreme likelihoods, such as those assigned to HSM by the proponents of Zoonosis, is similar to strawmanning in human debate and can demolish an otherwise valid probabilistic analysis. Following is a semi-formal definition of the problem and how to avoid it:

- Our goal in a probabilistic analysis is to estimate Bayes factors.

- A Bayes factor is the ratio of conditional probabilities.

- A conditional probability p(E|H) is the probability the evidence E will occur, assuming H is true.

- In real-world situations, there are many ways E can occur, so p(E|H) should integrate over all those ways (using “1−∏(1−pi)”).

- In practice, focusing only on the most common way is usually accurate enough, and dramatically reduces the required work, as real-world data tends to have extreme distributions, such as a power law distribution.

- This is the “best explanation” – the explanation that maximizes the likelihood of the hypothesis – and making a serious effort to find it is steelmanning.

- A mistake in this step, even just choosing the 2nd best explanation, could easily result in orders-of-magnitude errors.

- To reduce such mistakes, it is crucial to seriously meet the requirement above of “assuming H is true”. That is a very unintuitive process, as humans tend to feel only one hypothesis is true at any time. Rational thinkers are open to replacing their hypothesis in the face of evidence, but constantly switching between hypotheses is difficult.

- The example we like to give for choosing a best explanation is in DNA evidence. A prosecutor shows the court a statistical analysis of which DNA markers matched the defendant and their prevalence, arriving at a 1E-9 probability they would all match a random person, implying a Bayes factor near 1E9 for guilty.

But if we try to estimate p(DNA|~guilty) by truly assuming innocence, it is immediately evident how ridiculous it is to claim only 1 out of a billion innocent suspects will have a DNA match to the crime scene. There are obviously far better explanations like a lab mistake, framing, an object of the suspect being brought by someone to the scene, etc. The goal is to truly seek which explanation is most likely for each hypothesis, using the specifics of each case. - Furthermore, it’s important to not only find the best explanation but honestly think about how well we understand the issue and estimate how likely it is there is some best explanation that still evades us (i.e. that we are currently estimating the 2nd best explanation or worse). This too is obvious to researchers who know not to go publish immediately upon finding something, but rather go through rigorous verification that their finding doesn’t have some other mundane explanation.

- So, the more complex the issue is, and the weaker our understanding of it, the less justified we are in claiming a low conditional probability. In frequentist terms, the question we should ask ourselves: How often did I face a similar issue only to later find there was a much more mundane explanation? Suppose it’s 1 in 10, then the lower bound on our p is 0.1 times however frequent that mundane explanation happens (say 0.2, for a total of 0.02)

Claiming something like p=0.0001 in a situation where we don’t have a perfect understanding of the situation is a catastrophic mistake. - For well-designed replicated physics experiments p could reach very low (allowing for the five sigma standard), but when dealing with noisy complex systems involving biology, human behavior, exponential growth, etc. it is extremely hard to confidently claim that all confounders (i.e. better explanations for the finding) were eliminated, so claiming a very low p is an obvious mistake.

- The last guideline is to also examine our confidence in our process. As we examine best explanations, we also need to account for the possibility that we made mistakes in that process itself.

Suppose the explanations for the DNA match are only “by chance” and “lab mix-up”, and suppose we examined the lab procedures and talked to staff and determined a mix-up was very unlikely, it still doesn’t make “by chance” the most likely explanation, since it is still possible our analysis was wrong, and the combined probability of our mistake and a mix-up (say 0.01*0.01) is still much higher than a chance match (1E-9).

To summarize: Estimating the Bayes factor requires estimating conditional probabilities, which requires finding the best explanation under each hypothesis, which can easily succumb to several pitfalls that cause catastrophic errors. To avoid those: a) Seek and honestly evaluate best explanations under the assumption the hypothesis is true, b) Estimate the likelihood that there is some better explanation that is yet to be found – the more complex the issue is, the higher the likelihood, and c) Estimate the likelihood of mistakes in the estimates themselves.

How to measure p(HSM|Lab Leak, Wuhan)

Given the insights above, we need to put a serious effort into finding the most likely reason an early cluster of Covid cases would form at HSM.

The reason this question focuses on an early cluster is because early isolated cases of Covid are unlikely to be detected – either a) the person doesn’t even get treated, or b) there is no reason to think they have a new pandemic virus without expensive diagnosis and research (especially true during flu season).

Only a cluster of cases in the same location with enough severely ill people is likely to get noticed, especially if it happens to be in a location with wildlife.

We provide three methods to estimate this number, all of them supporting a conclusion that this conditional probability is over 1%. Given that each of these provides a minimum estimate, and some are independent alternative explanations for an HSM cluster, a reasonable final estimate would be 5-10%. We still conservatively assign it 1%, which is enough to make this evidence negligible.

Method 1 – Factors in HSM

HSM is not some random location in Wuhan, and it has a number of environmental factors that significantly increase the likelihood of forming an early Covid cluster compared to other busy locations:

- High traffic, making an initial infection likely in the early stages of the pandemic. With 10,000 visitors a day, having a first infection becomes likely when there are still only a couple hundred infected all over Wuhan.

- Many permanent residents (over 1,000 tenants) who can amplify the virus locally. This is essential in order to have enough cases in the same place that would form a cluster that health professionals will notice. There aren’t that many such locations in a city.

- Many cold wet surfaces, which allow the virus to survive for weeks rather than hours.

- Enclosed space, with low ventilation. Interestingly, the area of HSM with more positive samples, which some tried to associate with the wildlife stores, also happens to be the least ventilated area, with no connection to the outside.

- Low hygiene, visible in photos and videos of the market before the shutdown.

- A mahjong hall frequented by the vendors, which could act as an internal superspreading location, greatly accelerating initial infections. Indeed, many of the earliest cases played mahjong (page 44 here).

Importantly, most of these factors have an exponential contribution, meaning that even a mild advantage could cause HSM to host a large portion of total cases within just a few weeks.

The probability of HSM forming an early cluster, given human infections in Wuhan, is estimated as follows:

- First we count how many locations in Wuhan could form an early cluster. For this we need a location that has the following parameters simultaneously:

- Enough permanent residents that they could produce enough hospitalized cases to make the cluster noticeable – this excludes locations like public transportation and small offices and buildings.

- The permanent residents need to interact enough to infect each other – this excludes locations like apartment buildings.

- Has enough incoming traffic to catch an infection early in the pandemic – this excludes most offices and factories that don’t serve customers.

- Has conditions that allow rapid exponential growth within the population – this excludes hospitals, which have good hygiene and isolation practices, open-air markets, and schools with young people who are unlikely to infect each other.

- The famous paper by Worobey et al. attempted a similar analysis and concluded that 1676 sites in Wuhan were superior to HSM in terms of superspreading potential. We looked at their data in detail and found that it was based on several false assumptions. In fact, given the above requirements, we couldn’t identify a single location in their list that was superior to HSM.

Large hospitals are the only plausible locations, as they have many permanent residents (staff and patients), and are likely to receive early cases. Still they’re trained in hygiene and controlling respiratory diseases, and anyway, there are only a handful of large hospitals in Wuhan, so they have little effect on the estimate. - Turning these insights into a number: There should be at most a few thousand places the size of HSM or larger (since it houses 1/10000 of Wuhan’s population, and most people are not part of a large organization). Given that each of the above factors eliminates a significant portion of such locations, we should at most be left with 100, giving a final probability of over 1%.

Method 2 – Other SARS 2 early clusters

As previously explained, the zoonosis case relies on the claim that only once in a few thousand non-zoonotic outbreaks, would the first detected cluster be associated with a market like HSM. Contrary to this claim, an empirical analysis reveals that seafood markets and facilities repeatedly formed initial Covid clusters following a period of zero infections. This was observed in 2 out of 5 large outbreaks in China in 2020 (Xinfadi and Dalian), as well as in outbreaks in Thailand and Singapore:

- For the Xinfadi outbreak in June 2020: among the 368 persons isolated and treated, 272 (73.9%) had epidemiologic links to the market—169 (46%) were market workers and 103 (28%) were visitors. All the remaining 96 (26%) were close contacts of the other cases. More specifically, the seafood market within Xinfadi had the most infections.

Incidentally, this is markedly different from HSM, where most of the early cases could not be connected to it. - For the Dalian outbreak in July 2020, the outbreak was in Dalian Kaiyang World Seafood, a major seafood processing facility. This was the first local outbreak reported after having no new local infections in Dalian for 111 consecutive days.

- In Thailand in mid-December 2020, after 6 months of near zero infections, more than 1,300 cases were traced to a seafood market in Samut Sakhon, a coastal province near Bangkok.

This case bears several eerie similarities to HSM, including the earliest case being a shrimp vendor.

“Nearby, razor wire and police guards blocked access to the Klang Koong, or Central Shrimp, seafood market — one of Thailand’s largest — and its associated housing, the epicenter of the new cluster.

Thailand’s Disease Control Department said Sunday that they found 141 more cases linked to the market outbreak. On Saturday, the department reported 548 cases, Thailand’s biggest daily spike, sending shockwaves through a country that has seen only a small number of infections over the past several months due to strict border and quarantine controls.

The new outbreak has been traced to a 67-year-old shrimp vendor at the seafood market.”

- In Singapore, a cluster of nearly 1200 cases was linked to a fishery port (where seafood was sold to the public) and wet markets. This too happened months after zero Covid.

It’s important to highlight the distinct nature of these early clusters compared to regular superspreader events. Early clusters are exceptionally rare because zero Covid periods were infrequent worldwide, and typically, each period would yield only one early cluster. The occurrence of two such cases in Thailand and Singapore, as well as 2 out of 5 major clusters during China’s 2020 zero Covid period, underscores their significance.

Most likely, the cold wet surfaces abundant in seafood markets provide a major advantage compared to other crowded locations.

To estimate this probabilistically we place these four cases in the numerator of a fraction, where the denominator represents all identified early clusters following zero Covid periods. Such a denominator is not accurately known, as early clusters are not always identified or documented. Given that not many countries achieved zero Covid, and often the early cluster is not easy to find, we place an upper limit of 100, for a ratio of over 4%. There could be some differences between HSM and these markets (one possibility discussed below), leaving us enough leeway to confidently claim the conditional probability is above 1%.

Those who, like Scott, were impressed by the coincidence that the pandemic started in the city of WIV, and then were more impressed by the coincidence that it started in a market hosting wildlife, should now be even more impressed by the coincidence that a shrimp vendor is again the index case in an early cluster. How many people are shrimp vendors? 1 in 100,000?

This kind of rules-of-thumb thinking is bound to result in wrong conclusions. There is sadly no alternative to a proper rigorous probabilistic analysis of all evidence using a methodology that avoids human bias.

A common objection to this method is that these outbreaks are caused by cold-chain products brought into these markets. However, this still fails to explain why markets form these early clusters and not the many other places where cold chain products are delivered to. Additionally, this only demonstrates the importance of cold wet surfaces in preserving SARS2 infectivity, further strengthening the hypothesis in method 1 that a crowded location with many wet surfaces like HSM is highly conducive for rapid SARS2 spread. Last, it also opens the possibility that the HSM outbreak was also caused by cold-chain products. This would reduce the significance of Wuhan being the outbreak location (as the product could have come from anywhere), but since the other evidence for lab-leak is so strong, Wuhan can be given no weight and still lab-leak would be highly likely – Rootclaim’s conclusion will only drop from 94% to 92%.

Method 3 – China CDC Move

In the debate we provided an alternative explanation for HSM forming an early cluster: It did host one of the first cases, but that was a result of the fact Wuhan CDC was moving just next to the market during the months before the outbreak, creating plenty of opportunities for a leak through WIV cooperation with CDC. For example, an infected WIV worker infects a CDC colleague who goes to the market for lunch, or contaminated WIV equipment is transferred to the new CDC location and infects a mover who then visits the market.

This mistake was also made by both judges. Even if you choose to believe HSM does not have any special properties that make it a far more likely early cluster location (method 1), and you’re confident it is markedly different than the other markets that formed early clusters (method 2), that only means you need to revert to our alternative hypothesis which was that the spillover was due to the CDC move right next to HSM. While we did not view this as the best explanation, it immediately becomes the best one for anyone choosing to reject other explanations.

It is hard to provide an accurate estimate for this, but the following should be close enough:

- Remember we still need many permanent residents in one space for a noticeable cluster to form – such locations should not account for more than 10% of Wuhan residents.

- The proximity to the CDC should account for at least a 10x advantage for HSM, relative to these other locations.

- This makes the supposed 1/10,000 coincidence a 1/100, which again supports the 1% conditional probability estimate.

Note that these are just the three methods we identified. To continue to believe the extreme p=1/10000 or p=1/000, you also need to be very confident there aren’t other explanations that were not yet identified. More generally, such extreme numbers are not possible outside very controlled environments where all confounders can be reliably eliminated (more on this below).

In more intuitive terms: to claim 1:10000, it is insufficient to state, “I didn’t see enough evidence to be convinced HSM is not some random location in Wuhan.” Instead, one must assert that “The claim that the conditions in HSM make it a likely location for an early cluster is utterly ridiculous. I understand this claim so deeply that I attribute less than 1% chance of it being true. (Otherwise, that becomes a superior explanation, at 1% * 1%) Furthermore, I analyzed all other initial clusters in seafood markets and facilities in China, Thailand, and Singapore. I am over 99% certain that these clusters are entirely distinct from HSM and do not increase the likelihood of its origin. Additionally, I evaluated all alternative hypotheses, such as the CDC’s proximity to HSM, and found that there is almost no chance that they would cause a leak. Additionally, I analyzed the outbreak dynamics thoroughly and am over 99% convinced that there are no other strong biases towards HSM that have not yet been discovered.”

There is simply no way to achieve this level of confidence.

How to measure p(HSM|Zoonosis, Wuhan)

We should now do the same for the other conditional probability. Here the common mistake is to miss the hindsight bias in assuming HSM is a likely spillover location, given zoonosis. The most prominent example is pointing to a photo of a raccoon dog that a virologist had taken in HSM years before, implying there was some premonition.

On the surface this may look like steelmanning – searching for a way to assign a high conditional probability. But steelmanning doesn’t mean just making up reasons for a high number. We need to find the highest number that can be reliably supported.

The raccoon dog photo and the identification of wildlife in HSM don’t meet that requirement as they are a result of hindsight bias.

First, there is no premonition in the raccoon dog photo. The virologist visited HSM because he was visiting WIV, and it is the largest wet market in Wuhan. Ironically, the photo actually demonstrates yet another possibility for how a WIV leaked virus can reach HSM.

Second, the picture was noted after the outbreak, so we can’t quantify its significance without evaluating how many other things did virologists document, which would seem interesting in hindsight

Same goes for wildlife in HSM. How many locations other than markets provide an interface with wildlife? Were markets actually identified in advance to be high-risk spillover locations or only in retrospect?

Following a question on this from Scott, we decided to dig further and did an unbiased search to better estimate the strength of this coincidence, as follows:

- Searched [wildlife -Covid “spillover locations”] prior to 2019.

- The fourth result was the first to have relevant information. It was the famous PREDICT plan by USAID (PDF).

- Scanned for relevant mentions

- This is the most relevant quote. Markets are not mentioned.

High-risk interfaces for zoonotic viruses transmitted by direct and indirect contact transmission included contact with wild animals in and around their dwellings and in agricultural fields (Figure 6). Occupational exposure associated with working with wild animals (veterinarians, researchers, and workers in laboratories) was also frequently reported.

- This text repeats several times with variations, including one instance where it discusses which locations should be surveilled, and proposes to expand the search to more locations, only then suggesting markets, indicating these are a lower priority risk:

Other interfaces were also targeted by surveillance to more fully investigate and rank risks for potential virus transmission, including wild animal farms; markets and restaurants; other sites on the food value chain; sites with ecotourism; and wildlife preying on livestock, raiding crops, and causing public safety hazard.

- Although markets are mentioned many times throughout the document, they are mostly discussed in relation to prevention rather than spillover because they are easy to regulate.

- Markets are also mentioned as one of the spillover locations for SARS1. To estimate the rate there we have a more specific study. It found that out of 23 early cases, 9 were connected to wildlife. Of these, 7 were restaurant chefs, one bought produce for a restaurant (so visited markets but didn’t work there), and one sold snakes at a market.

The relevant study cited in PREDICT includes a passage that identifies markets as one of twelve potential spillover locations:

“Transmission interfaces involving wildlife were stratified by direct and indirect contact transmission and summarized in categories describing human contact as follows i) wild animals in and around human dwellings, ii) wild animals hunted, iii) wild animals consumed, iv) wild animals kept as pets, v) wild animals housed in laboratories, vi) wild animals sold in markets, vii) wild animals kept in zoos and sanctuaries, viii) wild animal exposure during agricultural activities, ix) wild animal exposure during ecotourism activities, x) wild animal exposure during wildlife management activities in protected areas, xi) virus exposure in laboratory settings (lab pathogen) and xii) virus exposure via contaminated water.”

It is somewhat ironic that prior to Covid, labs were considered a more likely spillover location than markets.

Finally, we’ll try to quantify the conditional probability of an HSM spillover and early cluster, assuming zoonosis as the origin and Wuhan as the location, given this data:

- Markets are listed as one of 12 spillover locations, and in lower priority.

- A similar number is known from SARS1 where we have 1 out of 9 wildlife related cases being in a market. There were 14 more where the connection to wildlife is unknown so it likely happened in some rural location.

- HSM is only one of 4 markets with wildlife in Wuhan, albeit the largest one.

- A spillover at HSM does not necessarily mean the early cluster will form there, but it’s likely, so we’ll ignore that.

Multiplying the share of markets (1 and 2) by the share of HSM within markets (3), we converge to around 3-5%.

Our original estimate was that HSM should account for 10% of zoonotic spillover cases in Wuhan. Following this more detailed analysis we now realize this was too high. In most cases, an animal-to-human transmission would not result in the first cluster occurring in a wildlife location at all. The spillover would likely occur in some rural area, unnoticed, and then spread to Wuhan (or another city) through human contact, until forming a noticeable cluster somewhere. Interestingly, this may mean that even if SARS2 was zoonotic in origin, it is unlikely that the spillover happened in HSM!

Advanced note: This analysis is a bit simplified as it doesn’t take into account that Wuhan has much less of these interfaces than other places in China (a city doesn’t have many farms, and wildlife consumption is not popular outside south China). However this cancels out with the prior of having the outbreak start in Wuhan. Since we didn’t discount the prior of Wuhan due to this lower risk, any increase in one will need to be accompanied by a decrease in the other. To keep it simple, we ignore it in both.

The remarkable lack of evidence

The absence of evidence for any involvement of wildlife in the HSM outbreak seems hard to explain.

- All the animal samples in the market or the farms supplying it were negative.

- No evidence of positive infections among animal vendors, not even rumors.

- Early infections are distributed uniformly across the West side of the market. They are not centered on any interesting location. This is more compatible with early infections coming from the mahjong room – matching the multiple reports of early cases being mahjong players.

- Animal cages don’t have high SARS2 reads, whereas several stalls with infected vendors do.

- Positive SARS2 environmental samples are not positively correlated with wildlife stalls or wildlife genetic material.

This is in addition to the following evidence contradicting an HSM spillover in general:

- Majority of early cases could not be connected to the market. This is in contrast to the later outbreak in Beijing, where 100% of cases could be traced to the market.

- Chen and Connor Reed are both indicative that the earliest cases are not in the market. While there is some uncertainty about each of them alone, together they are fairly strong.

- Market cases are all from lineage B, while there are many cases with the more ancestral lineage A outside the market.

Some of these claims are contested by the other side and we included only those that we’re confident in – see a more detailed discussion below.

Specific comments

Following are comments on specific statements in Scott’s post. While of lesser importance compared to the main mistake above, they may help get a better understanding on the origins of Covid and how to better do probabilistic inference.

About Sore losing

We’d like to place this comment first (the rest are in the order they appear), as it is a repeating complaint we get that we are ‘doubling down’ on a bad decision, by not changing our conclusion to zoonosis following the loss of the debate.

Scott writes:

Saar says the debate didn’t change his mind. In fact, by the end of the debate, Rootclaim released an updated analysis that placed an even higher probability on lab leak than when they started.

In his blog post, he discussed the issues above, and said the judges had erred in not considering them. He respects the judges, he appreciates their efforts, he just thinks they got it wrong. Although he respected their decision, he wanted the judges to correct what he saw as mistakes in their published statements, which delayed the public verdict and which which Viewers Like You did not appreciate:

Referring to this manifold market blaming us of being sore losers, because we didn’t update our analysis towards zoonosis (It additionally correctly criticized an initial 99.8% probability, which was due to a rushed sensitivity analysis that was quickly corrected, giving 94%).

This is a misunderstanding of what Rootclaim does. All we do is implement a methodology for minimizing probabilistic inference mistakes. We improve it over time with experience, and at this point are very confident it is superior to any other inference method.

Our conclusions are the result of running the methodology on the evidence. For the conclusion to change there needs to be an update in either the methodology or the evidence.

The debate hardly discussed the methodology nor our Covid origins probabilistic model, so it didn’t provide any helpful feedback in that aspect. It did allow us to more deeply understand the evidence, which we definitely updated in the new version of our analysis.

Reading the judges’ reports was also unhelpful, as the probabilistic inference mistakes there were patently obvious to us (remember we’re doing this for over a decade). We published a report on these mistakes, and so far no one was able to point to any problem with it.

So, to be clear – We fully integrated into our new analysis all the new information from the debate as well as the feedback we received following the debate. It so happened that it strengthened the probability of a lab-leak rather than weakened it. We understand this looks from the outside as stubborn, sore losing, or unscientific, but there’s not much we can do – that is the process we follow, and this is its result. We won’t publish a bad analysis just to look noble.

Spatial spread of environmental samples in HSM

Scott shows a map of the environmental samples taken in HSM and explains this supports zoonosis (note he confuses cases and samples here):

A map of cases at the wet market itself shows a clear pattern in favor of the very southwest corner:

The southwest corner is where most of the wildlife was being sold. Rumor said that included a stall with raccoon-dogs, an animal which is generally teeming with weird coronaviruses, and is a plausible intermediate host between humans and bats:

However, this interpretation is misleading as it primarily reflects increased sampling in the area where wildlife is sold. Once this is corrected, the chart becomes less impressive. When you consider there are likely also implicit biases, such as more meticulous sampling in wildlife stalls, or resampling after receiving a ‘surprising’ negative sample, it’s clear this map has little evidential weight.

Incidentally, while preparing for the debate, we discovered this area also happens to be the least ventilated in HSM.

Why cases are not centered around WIV

Scott quotes Peter, who implies that under the lab-leak hypothesis, we would expect the confirmed early cases to be centered around the WIV.

Peter: The first officially confirmed Covid case was a vendor at the Wuhan wet market. So were the next four, and half of the next 40. A heat map of early cases is obviously centered on the wet market, not on the lab.

However, cases are not expected to center on the lab. The lab is not spraying viruses into the air or hosting thousands of locals daily. If a worker gets infected, they spread the virus to their friends and family at completely different locations.

About claims made from early case data

This is a good place for a general comment about any claims made from the early case data provided by Chinese authorities, which makes up for a good chunk of zoonosis claims.

The data pertaining to the early cases are unreliable and potentially manipulated, making it extremely difficult to derive clear conclusions. A detailed 194-page analysis by Gilles Demaneuf offers some insight into the matter, but our recommendation is to simply acknowledge there is great uncertainty that makes it impossible to draw any high confidence conclusions.

What is worth noting is that China did not publish the most obvious action they should have taken, which is contact tracing of all early cases. Since it is improbable that contact tracing was not conducted, the lack of public disclosure suggests that the findings might have contained unfavorable findings.

Regarding session 1 summary

One of the main arguments we raised in the debate was not mentioned at all in Scott’s post.

All the evidence trying to support a spillover at the market is based on complex models with many single points of failure, built from unreliable and biased data. Therefore, it is difficult to give this evidence significant weight as there is always a possibility of errors in the data or its interpretation. More on this in the UFO comment below.

The lack of infected animals

Scott quotes Peter explaining why he thinks it isn’t significant that no infected animals were found in HSM:

Peter: Raccoon-dogs were sold in various cages at various stalls, separated by air gaps big enough to present a challenge for Covid transmission, and there’s no reason to think that one raccoon-dog would automatically pass it to all the others. The statistical analysis just proves there were many raccoon-dogs who didn’t have Covid. But you only need one.

To illustrate what a market looks like in a real zoonotic pandemic, consider this study from SARS1. The researchers went to a random market and sampled the wildlife sold there. 4 of 6 civets sampled were positive, and 3 of them were phylogenetically distinct (i.e. infected in completely different places).

Intermediate genomes

Scott quotes Peter’s attempt to discredit intermediate sequences that contradict the zoonosis double spillover claim.

The scattered cases of “intermediates” are sequencing errors. They were all found by the same computer software, which “autofills” unsequenced bases in a genome to the most plausible guess. Because Lineage B was already in the software, depending on which part of a Lineage A virus you sequenced, you might get one half or the other autofilled as Lineage B, which looked like an “intermediate”. We know this because all the supposed “intermediates” were partial cases sequenced by this particular software. We can confirm this by noting that there are too many intermediates! That is, where Lineage A is (T/C) and Lineage B is (C/T), the software found both (T/T) “intermediates” and (C/C) “intermediates”. But obviously there can only be one real intermediate form, and we have to dismiss one or the other. But in fact we can dismiss both, because they were both caused by the same software bug.

While Peter had a good point about the C/C sequences, he was unable to provide a good explanation for the T/T sequences. And indeed new evidence indicates these are likely to be real. This alone makes an HSM spillover unlikely, delivering a major blow to the zoonosis hypothesis.

The rarity of BANAL-52

Scott explains that Covid’s closest known relative, BANAL-52, is rare and so it’s highly unlikely the WIV would’ve had it available as the starting point to engineer Covid.

“But suppose they did make more trips. Given the amount of time between the DEFUSE proposal and Covid, if they kept to their normal virus-collection rate, they would have gotten about thirty new viruses. What’s the chance that one of those was BANAL-52? There are thousands of bat viruses, and BANAL-52 is so rare that it wasn’t found until well after the pandemic started and people were looking for it very hard. So the chance that one of their 30 would be BANAL-52 is low.”

This is a basic mistake. SARS2 is not based on BANAL-52 but a relative of it. There is nothing unlikely here.

The reliability of Connor Reed

A British expatriate in Wuhan, Connor Reed, says he got sick in November, three weeks before the first wet market case. Later the hospital tested his samples and said it was Covid. Another paper reports 90 cases before the first wet market one.

Peter: The British man was lying. The case wasn’t reported in any peer-reviewed paper. It was reported in the tabloid The Daily Mail, months after it supposedly happened. He also told the Mail that his cat got the coronavirus too, which is impossible. Also, to get a positive hospital test, he would have had to go to the hospital, but he was 25 years old and almost no 25-year-olds go to the hospital for coronavirus. His only evidence that it was Covid was that two months later, the hospital supposedly “notified” him that it was. The hospital never informed anyone else of this extremely surprising fact which would be the biggest scientific story of the year if true. So probably he was lying. Incidentally, he died of a drug overdose shortly after giving the Mail that story; while not all drug addicts are liars, given all the other implausibilities in his story, this certainly doesn’t make him seem more credible. And in any case, he claimed he got his case at a market “like in the media”

- Reed’s case is not a tabloid story. He was interviewed by dozens of other outlets, including The Guardian, and there are many video interviews of him available.

- About his cat getting Covid: Unclear why this discredits him. Connor Reed was not a coronavirus expert. He initially believed his cat had also contracted the same virus, was later probably told that it was unlikely and corrected it to say his cat had a “feline coronavirus”. It’s also worth mentioning that contrary to Peter’s claim, cats can be infected by Covid-19.

- He went to the hospital after feeling very bad, like many young people who got pre-omicron Covid (especially expats), received medicine and was dismissed. Nothing special about it.

- There is of course an obvious reason why his confirmed test might not be published as “the biggest scientific story of the year”.

- The drug overdose was not “shortly after”, but a year later, after he returned to the UK, and it happened due to bad mixing of drugs with his university flatmate – not alone under a bridge. At the time he was infected, he was an English teacher in Wuhan.

- Reed definitely did not claim he got infected at HSM. He mentioned a fish market where he does his regular shopping, which others just assumed to be HSM. This is near impossible: A single young man who lives 600m from his job would not do his ‘regular shopping’ in a wholesale seafood market that is a 3 hours round trip. Additionally, he doesn’t think he got it there, which would be weird if he regularly visited a location with hundreds of infections.

Overall, all attempts to portray him as an unstable, delusional person were unsuccessful. He is an ordinary person who very accurately described Covid-19 symptoms in real-time and claims to have received a positive test result. The timing and location matches the lab leak hypothesis and is impossible for the HSM claim. Therefore, they must discredit him.

One more thing: Reed’s case was badly misrepresented by Peter here. This was just one misrepresentation that we managed to catch, but there are likely many more that we haven’t, because our methodology allows us to focus on a small fraction of the evidence that is sufficient to reach an accurate conclusion, and invest much less effort in researching minor details.

This created the false impression that the evidence for zoonosis was richer and more reliable, which is another reason the debate swayed people towards zoonosis.

Claiming the FCS is not that unnatural

Covid’s furin cleavage site is admittedly unusual. But it’s unusual in a way that looks natural rather than man-made. Labs don’t usually add furin cleavage sites through nucleotide insertions (they usually mutate what’s already there). On the other hand, viruses get weird insertions of 12+ nucleotides in nature. For example, HKU1 is another emergent Chinese coronavirus that caused a small outbreak of pneumonia in 2004. It had a 15 nucleotide insertion right next to its furin cleavage site. Later strains of Covid got further 12 – 15 nucleotide insertions. Plenty of flus have 12 to 15 nucleotide insertions compared to other earlier flu strains.

Highly inaccurate. Despite years of focus on this weird 12nt clean insertion in SARS2, no one was able to produce anything remotely similar to it.

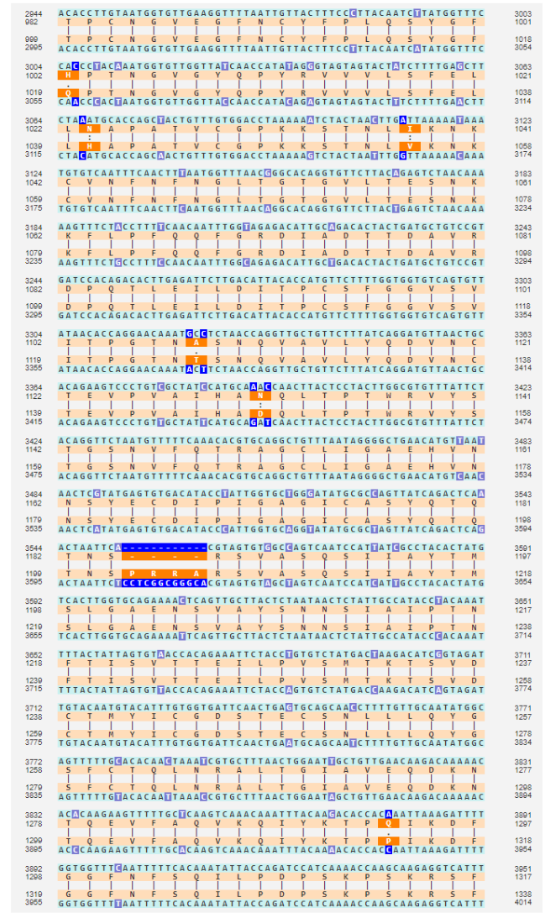

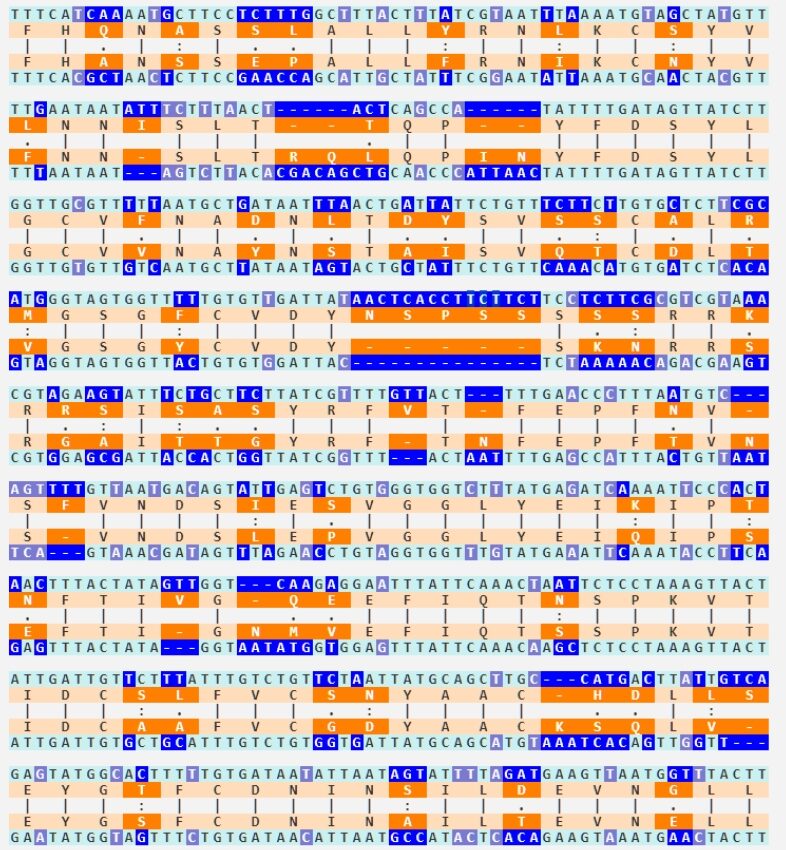

To understand how ridiculous the claim is that the HKU1 insertion looks just as engineered as SARS2’s, here are their alignments. Hopefully that should be enough.

SARS2 vs closest relative:

HKU1 vs closest relative:

The judges decision was not due to probabilistic inference mistakes

I’m focusing on this because Saar’s opinion is that the debate went wrong (for his side) because he didn’t realize the judges were going to use Bayesian math, they did the math wrong (because Saar hadn’t done enough work explaining how to do it right), and so they got the wrong answer. I want to discuss the math errors he thinks the judges made, but this discussion would be incomplete without mentioning that the judges themselves say the numbers were only a supplement for their intuitive reasoning.

This is confusing two different things. The judges indeed had reservations about doing a full probabilistic analysis. But they definitely relied heavily on probabilistic thinking when evaluating the strength of specific evidence, most notably in wrongfully concluding HSM is strong evidence by calculating the probability of the index case being in a group of 1000 HSM workers out of 10 million Wuhan residents. As we showed, this probabilistic inference mistake alone was enough to reach a wrong conclusion.

Are extreme likelihood ratios possible?

Saar had specific arguments against this, but he also had a more general argument: you should rarely see odds like 1/10,000 outside of well-understood domains.

Indeed, this is possible in highly controlled environments like physics experiments and computers, or when highly accurate statistics are available using a good reference class.

This is not currently the case in the origins debate, and we should therefore not see such numbers there. In the case of HSM we specifically pointed to the multiple mistakes people made in reaching this wrong number.

More in point 12 of our post here: “For well-designed replicated physics experiments p could reach very low (allowing for the five sigma standard), but when dealing with noisy complex systems involving biology, human behavior, exponential growth, etc. it is extremely hard to confidently claim that all confounders (i.e. better explanations for the finding) were eliminated, so claiming a very low p is an obvious mistake.”

Can steelmanning cause you to think the sun won’t rise tomorrow?

This makes total sense, it’s absolutely true, and I want to be really, really careful with it. If you accept this reasoning too hard you can convince yourself that the sun won’t rise tomorrow morning. All you have to do is propose 100 different reasons the sunrise might not happen. For example:

- The sun might go nova.

- An asteroid might hit the Earth, stopping its rotation.

- An unexpected eclipse might blot out the sun.

- God exists and wants to stop the sunrise for some reason.

- This is a simulation, and the simulators will prevent the sunrise as a prank.

- Aliens will destroy the sun.

…and so on until you reach 100. On the one hand, there are 100 of these reasons. But on the other, they’re each fantastically unlikely – let’s say 99.9999999999% chance each one doesn’t happen – so it doesn’t matter.

But suppose you’re good at reasoning and you realize that you should never see numbers like 99.9999999999%. You might think you have a great model of how eclipses work and you know they never happen off schedule, but can you be 99.9999999999% sure you understood my astronomy professor correctly? Can you be 99.9999999999% sure you’re not insane, and that your “reasoning” isn’t just random seizings of neurons that aren’t connecting to reality at any point? Seems like you can’t. So maybe you should lower my disbelief in each hypothesis to something more reasonable, like 99%. But now the chance that the sun rises tomorrow is 0.99^100, aka 36%. Seems bad.

As previously stated, the Rootclaim methodology has no problem reaching high probabilities in cases like these where physics are involved or strong statistics exist. It’s just not applicable to the origins question.

Neglecting dependencies in evidence

Even aside from the failure mode in the sunrise example above (where people are too reluctant to give strong probabilities), it fails because people don’t think enough about the correlations between stages. For example, maybe there’s only 1/10 odds that the Wuhan scientists would choose the suboptimal RRAR furin cleavage site. And maybe there’s only 1/20 odds that they would add a proline in front to make it PRRAR. But are these really two separate forms of weirdness, such that we can multiply them together and get 1/200? Or are scientists who do one weird thing with a furin cleavage site more likely to do another? Mightn’t they be pursuing some general strategy of testing weird furin cleavage sites?

And indeed Yuri provided a satisfying hypothesis that explains both of these: Some sarbecoviruses have PAAR in that location, so researching its mutation into PRAR and then PRRAR is an interesting project.

It is worth noting that this would also explain the use of a 12nt insertion – It would be required for such research, as there is no ‘P’ present in the BANAL-52 family.

How strong is the FCS “coincidence”

Likewise, the furin cleavage site really is weird. I didn’t feel like either side did much math to quantify this weirdness. Naively, I might think of this as “30,000 bases in Covid, only one insertion, it’s in what’s obviously the most interesting place – sounds like 30,000-to-one odds against”.

Here is a quick calculation of the FCS coincidence:

Based on the number of SNV mutations relative to BANAL-52, and using known statistics on long insertions, SARS2 should have only around 0.01 long insertions. Another way to appreciate this is to note that not only does SARS2 have no long insertions relative to its closest relatives, it doesn’t have any insertions, not even the far more common 3 nucleotides insertions.

Next, the probability of that clean long insertion occurring at the correct location is approximately 3000, not 30,000, due to several locations being relevant. Additionally, the sequence being from a foreign source increases the probability by about 10x. Therefore, the overall probability is approximately 1 in 30,000,000. This is before considering this is the first FCS in this family, which is harder to quantify.

This calculation has no relevance in our methodology, as the methodology requires “steelmanning” all hypotheses (as explained above) and scientists have nowhere near enough understanding of FCSs to claim a 1 in millions confidence there is no better explanation for this unique FCS. We didn’t even bother to calculate this 30 million number (as Scott laments here) until we realized people don’t understand this concept. After a decade of dealing with these problems, it is often difficult to predict what others would find easier or harder to understand.

If you use 10,000x for HSM, you must use 30,000,000x for FCS.

If you use the more accurate 25x for FCS, then you must use 2x for HSM.

No picking and choosing!

Maybe if you add in some of the evidence that other viruses have insertions here, it becomes only 100-to-one against, but that’s still a lot.

As explained above, there is no evidence of similar insertions in any other virus.

Against that, a virus with a boring insertion would never have become a pandemic, so maybe you need to multiply this by however much viral evolution is going on in weird caves in Laos, to get the odds that at least one virus would have an insertion interesting enough to go global. Neither participant really tried to calculate this

This is of course one of the more trivial biases in probabilistic inference (texas sharpshooter / selection bias / multiple comparisons), and obviously, our methodology accounts for it in all analyses.

In this case we solve it by focusing only on pandemic-causing viruses, and comparing the different ways they could emerge.

Rootclaim’s big picture

The problem was, Saar couldn’t effectively communicate what his big picture was. Neither deployed some kind of amazingly elegant prior. They both used the same kind of evidence. The only difference was that Peter’s evidence hung together, and Saar’s evidence fell apart on cross-examination.

This is a common theme throughout Scott’s piece, conflating Peter’s superiority in debating real time, with what the actual evidence was. When examining only the written parts where each side could research properly, and not under time pressure, we believe it’s evident that all the zoonosis claims collapse while all core lab leak claims survive.

Scott’s post further amplifies this wrong impression by choosing to end each of the four sections with Peter’s comments. Scott said he’s done this because Peter seemed to go deeper into chains of rebuttals, such that most of his evidence stood unrebutted. While Peter was indeed impressive in his memory of details, his evidence definitely did not survive deeper scrutiny, and we specifically listed above strong rebuttals to the closing arguments of each of the sections (which were all included in the debate written material).

Having contradicting strong evidence

Saar brought up an interesting point halfway through the debate: you should almost never see very high Bayes factors on both sides of an argument.

That is, suppose you accept that there’s only a 1-in-10,000 chance that the pandemic starts at a wet market under lab leak. And suppose you accept there’s only a 1-in-10,000 chance that Covid’s furin cleavage site could evolve naturally.

If lab leak is true, then there’s no problem with finding 1-in-10,000 evidence for lab leak, but it’s a freak coincidence that there was 1-in-10,000 evidence for zoonosis (and vice versa if zoonosis is true).

As explained above, even one 10,000x factor is unlikely to be found in the Covid origins question. It is true that when it is possible (controlled environments), then you should definitely not see two opposing ones – that would indicate one of them is not really 10,000x and you did not steelman properly.

Nevertheless, it is possible to reach high confidence when examining multiple pieces of evidence, which is another reason why having good inference is superior to having good evidence. While smoking-gun evidence is hard to come by, reaching smoking-gun levels of confidence is possible through good inference.

There is something similar in scientific discourse: We are much more impressed by multiple independent studies replicating the same result at a modest p-value than a single one claiming a very strong p-value.

The similarity of zoonosis claims to UFO claims

I’m potentially sympathetic to arguments like Saar’s. Imagine a debate about UFOs. Imaginary-Saar says “UFOs can’t be real, because it doesn’t make sense for aliens to come to Earth, circle around a few fields in Kansas, then leave without providing any other evidence of their existence.” Imaginary-Peter says “John Smith of Topeka saw a UFO at 4:52 PM on 6/12/2010, and everyone agrees he’s an honorable person who wouldn’t lie, so what’s your explanation of that?” Saar says “I don’t know, maybe he was drunk or something?” Peter says “Ha, I’ve hacked his cell phone records and geolocated him to coordinates XYZ, which is a mosque. My analysis finds that he’s there on 99.5% of Islamic holy days, which proves he’s a very religious Muslim. And religious Muslims don’t drink! Your argument is invalid!” On the one hand, imaginary-Peter is very impressive and sure did shoot down Saar’s point. On the other, imaginary-Saar never really claimed to have a great explanation for this particular UFO sighting, and his argument doesn’t depend on it. Instead of debating whether Smith could or couldn’t have been drunk, we need to zoom out and realize that the aliens explanation makes no sense.

This is a parable we like and often use that is actually quite relevant to the zoonosis claim:

All evidence for UFOs is always ‘almost there.’ If only the camera had 3x more zoom, we would finally have a clear UFO photo. If only the building didn’t block the view at the critical moment in the video, if only the abductee had an audio recorder running.

When you have a lot of evidence that is ‘almost’ conclusive, instead of being an indication for the strength of your hypothesis, it likely indicates the presence of some filter between you and the evidence. In the case of UFOs – when we have good documentation it reveals there is a mundane explanation for the phenomena, which then prevents the evidence from becoming popular.

Therefore, the pattern of the UFO evidence does not support the UFO visits hypothesis, despite the supposed abundance of that evidence.

Zoonosis is similar in that all their evidence is based on complex models using unreliable data, with many single points of failure.

For example, the market cases are all lineage B – simple and robust evidence that it is not the source. Zoonosis proponents respond with a highly complex model that shows that lineage B was the first to jump to humans, and later another animal with a 2-mutation earlier variant happened to reach the same market and infect others, while no other animal infected any other human anywhere in the world. The model claims 98% confidence in this scenario, so zoonotic wins. Later, when major errors are found in the model, researchers are not deterred and come up with another complex model. And indeed, while preparing for the debate, an erratum was published on this lineage model, reducing its significance to negligible, which doesn’t stop proponents of zoonosis to continue to rely on this and other such models as strong evidence. This is a pattern of evidence indicative of motivated reasoning, allowing us to heavily discount such studies.

To be clear, lab leak proponents also have plenty of weak evidence like that, but we do not use it in our analysis, and for the same reason. However, unlike Zoonosis, lab-leak also has good evidence. There is no explanation for the Wuhan outbreak, for why an FCS arose with a very rare mutation type, why its sequence is from some unknown foreign source, why no animal host was found, why no other spillovers appear anywhere in the world. These are easy to understand claims, that can be statistically quantified, and have few points of failure (which is why no one was able to refute them). Zoonosis has exactly zero such evidence.

This is yet another example of why good inference tools are more important than a full understanding of all the evidence.

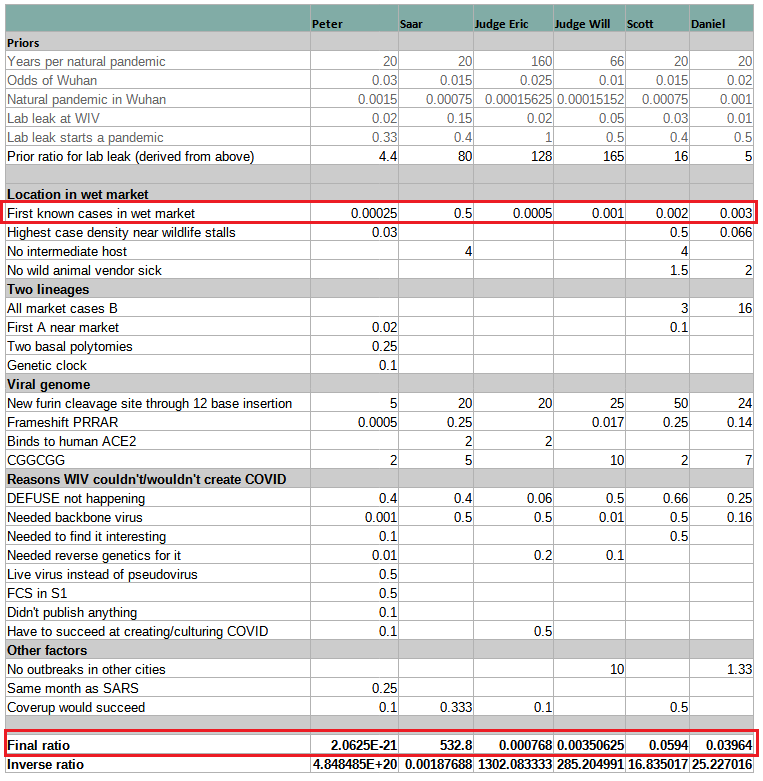

Comparing people’s probabilistic analyses

This very helpful table clearly illustrates how the mistake in interpreting HSM is the key to misunderstanding origins. All models assign more extreme probabilities to “First known cases in wet market” than the “Final Ratio” (except for Peter’s whose numbers are given half-jokingly). If you correct that mistake by replacing the wrong number with Rootclaim’s 0.5 and recalculate, everyone turns into supporting lab-leak or being roughly even. Specifically, Scott’s conclusion would change from its current 94% zoonosis to 94% lab-leak, which incidentally is identical to Rootclaim’s conclusion (although that is after our sensitivity analysis).

The key takeaway from this is that anyone who’s claiming zoonosis is more likely, but is unable to point to any major weakness in our analysis above of why HSM is negligible evidence, can be safely ignored.

The six estimates span twenty-three orders of magnitude. Even if we remove Peter (who’s kind of trolling), the remaining estimates span a range of ~7 OOMs. And even if we remove Saar (limiting the analysis to neutral non-participants), we’re still left with a factor-of-50 difference.

Using this as evidence of the weakness in probabilistic inference is a bit funny. We have 6 estimates that span a very wide range, so obviously this concept doesn’t work. It’s not important that 5 are by people who have never done a full probabilistic inference analysis in their life, and one is by a team doing it for a decade.

Additionally, Rootclaim’s number here is before the sensitivity analysis, which turns the 1:532 (99.8%) into 94%. The sensitivity analysis results in us rarely getting extreme numbers, so our conclusions actually span a fairly narrow range, and are not easily moved by small changes. Therefore, the generic complaint mentioned above does not apply to Rootclaim.

Lab-leak claims debunked?

Peter’s position is that, although the lab leak theory is inherently plausible and didn’t start as pseudoscience, it gradually accreted a community around it with bad epistemic norms. Once lab leak became A Thing – after people became obsessed with getting one over on the experts – they developed dozens of further arguments which ranged from flawed to completely false. Peter spent most of the debate debunking these – Mr. Chen’s supposed 12/8 Covid case, Connor Reed’s supposed 11/25 Covid case, the rumors of WIV researchers falling sick, the 90 early cases supposedly “hidden” in a random paper, etc, etc, etc. Peter compares this to QAnon, where an early “seed” idea created an entire community of people riffing off of it to create more and more bad facts and arguments until they had constructed an entire alternative epistemic edifice.

None of these claims were actually debunked, and anyway, they were either ignored or incidental in Rootclaim’s analysis.

Peter failed to weaken any of Rootclaim’s core evidence, while his only evidence – the HSM early cluster, is shown to be of negligible weight when using proper inference methods.

What will get people to trust Rootclaim?

If Saar wants to convince people, I think he should abandon his debates – which wouldn’t help even if he won, and certainly don’t help when he loses – and train five people who aren’t him in how to do Rootclaim, up to standards where he admits they’re as good at it as he is. Then he should prove that those five people can reliably get the same answers to difficult questions, even when they’re not allowed to compare notes beforehand. That would be compelling evidence!

We don’t think this would be convincing to a wide audience outside people who think like Scott. However, we don’t really have any better ideas, and would love to hear ideas from readers.

In general, the Rootclaim experience is highly frustrating – we spend years developing a new rigorous mathematical approach to answer important unanswered questions, but no one actually engages with the model itself or points to any flaws in it, but instead respond with standard flawed arguments about some evidence that ‘obviously’ contradicts a specific conclusion, without providing any rigorous explanation why it’s so obvious.

We’d love to hear suggestions for making our methodology more approachable and convincing to a wide audience. Thanks for helping!

Was China covering up zoonosis?

“Conspiracy theory” might be the wrong term here, because we already know there were several conspiracies. There was the conspiracy by the virologists to get the media not to talk about the lab leak. And there was a conspiracy by China to cover up the evidence on both sides. Peter pointed out that China wasn’t just motivated to cover up lab leak; they also covered up a lot of the evidence for zoonotic spillover (although Saar points out this coverup only started later, and doesn’t really affect his case). China’s “theory” is that the Covid pandemic started in Maine, USA, and reached Wuhan via a shipment of infected lobsters (really!). They were happy to be equal-opportunity coverer-uppers, hiding a lot of evidence for any story opposing this one.

This is untrue. They clearly said from the start this is a zoonotic spillover at HSM, and at least part of the government went to immense efforts to identify the animal, close farms, etc. (and of course couldn’t find any infected animal).

Only in late 2020 did they start suspecting an import from cold-chain products after having multiple outbreaks that seem related to cold-chain products.

Worth noting that it’s actually a reasonable conclusion to reach once you see the evidence goes against an animal spillover in HSM, and you’re incentivized against claiming a lab leak.

New evidence WIV was meant to do more DEFUSE work

Also, a new Freedom of Information Act request got early drafts of the DEFUSE grant proposal with new details, of which the most explosive was a comment by the American half of the team, reassuring the Chinese half that even though the proposal focused on American work to please funders, they would let the Chinese side do some “assays”. Lab leakers say this disproves the argument that, because DEFUSE said the work would be done in the US, the Wuhan Institute of Virology couldn’t/wouldn’t do advanced gain-of-function research.

(I asked Peter his response – he said the original draft of DEFUSE also said that the Chinese side would do “live virus binding assays”, and this isn’t the kind of gain-of-function research necessary to make Covid.)

This is a very narrow interpretation of this bombshell discovery (p. 235 here). Having such a comment on record is a clear indication that the DEFUSE proposal was dishonest about the division of work and they are likely to do more work at WIV, where it would likely be cheaper and require less safety regulations.

Pseudoscience is everywhere

If we don’t accept the judges’ verdict, and think lab leak is true, are we worried the zoonosis side has some misbehavior of its own? Yuri and Saar didn’t talk about that as much. High-status people misbehave in different ways from low-status people; I think the zoonosis side has plenty of things to feel bad about (eg the conspiracies), but pseudoscience probably isn’t the right descriptor.

We indeed don’t make a big deal about unscientific behavior of people who oppose the conclusions we reach. First, because we don’t view ourselves as proponents of those conclusions, but of our methodology, which we realize can sometimes cause a conclusion to change, suddenly placing us on the other side. Second, because our whole process is about overcoming human bias, we are well aware of these human weaknesses, and consider it part of the mechanism. We generally find equally bad reasoning on both sides of each analysis we make – this is just how humans are.

We similarly didn’t make a big deal of the many mistakes we found in Peter’s claims, because we know the number of mistakes doesn’t have any effect on the conclusion – we just evaluate the evidence that does survive scrutiny. Peter dedicated a lot of his time to pointing mistakes in lab-leak claims (which were either claims we didn’t make, were inconsequential to our conclusion, or were not actually mistakes) and in retrospect we realize this created a wrong impression regarding the weight of evidence of each side, and may have also contributed to the loss of the debate.

It is worth clarifying that the zoonosis side is definitely full of pseudoscientific claims, just like all sides of all hypotheses we ever analyzed. There is basically no evidence for zoonosis other than the results of repeating the following process:

- Let’s take unreliable, biased, manipulated data (early case data provided by China, mobile check-in data)

- Let’s develop a highly complex model with multiple single points of failure that provides an explanation that is in contradiction to obvious and simple to understand evidence supporting lab-leak (Pekar, Worobey).

- Whenever a mistake is found in those complex models either ignore it or correct it while claiming the model still stands, not realizing this is likely just one of many bugs and the whole work should be retracted.

Worth noting here that during our research for the debate, we alone found probably 10 catastrophic mistakes in these studies.

This may also be a good point to reflect on the full picture as claimed by the zoonosis side and appreciate how weird it is.

- A bat coronavirus infects another host.

- It circulates there in enough hosts and for a long enough time that it is able to acquire this clean FCS insertion – which nothing remotely close to it was ever seen in any natural virus.

- Two of these hosts are brought to HSM, which happens to reside in the same city as WIV, who were involved in plans to build a virus with these exact features. All of this in a city that is nowhere near bat habitats and far from south China where wildlife consumption is popular.

- For some reason, the host with the later version of the virus infects people first, and the earlier variant spills later. This claim is necessary because the alternative is to admit that despite lineage A and B being all over Wuhan, somehow only the later lineage B appears in the supposed spillover location.

- Other than these two animals that somehow reached the exact same location, no other host is known to infect anyone else. No animal is ever tested positive for ancestral strains. Of the millions of humans sequenced, not one was infected by a virus that is not downstream from Wuhan.

This is certainly not how other pandemics have started.

Compare this to the lab leak story:

- WIV did exactly the work they were interested in.

- As planned, they did it in BSL-2 without masks, so unsurprisingly, someone got infected.

- It spread through Wuhan unnoticed, infecting Reed and whoever infected Chen, later forming an early cluster at HSM, exactly as we later see happen in other cities.

Of the many objections raised to this scenario, only two have not been completely refuted: We’re not yet sure about the engineer’s exact motivations in choosing that specific FCS sequence, and we don’t know whether WIV found a relevant virus in their collection trips.

Scott’s reduction of the HSM 10,000x factor

I started with a 10,000x Bayes factor on the market, but it was extremely lightly considered and not really adjusted for out-of-model error. Based on our discussions, I divided by four based on Saar’s good point that the market represented less than 100% of the possible zoonotic spread opportunity in Wuhan (I cashed this out as it representing 25% of opportunity, though with high error bars). Then I divided by an extra factor of five representing some sort of blind outside view adjustment based on how strongly Saar holds his position (this was kind of also a decision to explicitly include potential outside-the-model error because that would make discussing it with Saar easier).

This little footnote is actually the key to the entire analysis. Correctly assessing this number determines what is the most likely hypothesis, and Scott simply handwaves two numbers without providing any explanation for why they are appropriate. This is in contrast to the Rootclaim model that divides the number into its three components, and uses multiple unbiased sources to calculate each.

The 25% number is equivalent to claiming that nearly all zoonosis spillovers happen in markets with wildlife (since HSM is only one of four such markets in Wuhan, albeit the largest), completely discounting that prior to 2020 scientists pointed to other locations as far more likely, and ignoring that in SARS1 markets were a rare spillover location. Our estimate of 3-5% is far more reliable and well sourced.

He then gives no weight at all to the conditions in HSM, implying an HSM vendor who interacts daily with many people in an unhygienic closed environment that was proven to form early clusters elsewhere, is no different from a random Wuhan resident. Again, our 1% estimate is far superior, as it uses three independent methods, all based on actual data.

The additional 5x factor he gave due to Saar’s strong position is not the best way to approach this. Steelmanning is not about arbitrarily increasing conditional probabilities. It is about truly considering alternative explanations and evaluating the strongest ones. Sometimes it could be 1000x and sometimes nothing. He should examine the actual quantitative arguments made to reach a 2x factor for HSM, and the data they’re based on, see if he can find any weaknesses, and update accordingly. Since there is a 250x difference at play here, this is the most important disagreement to focus on, as it has the most potential to sway the decision. The rest can wait.

Scott’s final number (500x) is based on highly biased estimates which cannot be justified. As shown, once this is corrected, Scott’s conclusion changes from 94% zoonosis to 94% lab-leak.

New addition: responses to Scott’s update

On April 9th, 2024, Scott posted a second blog post about the debate, addressing responses to his first post. This new post introduces several new mistakes, which we address below. However, the most important thing to note is that Scott does not address the main problem we pointed out in our original response above – that his whole conclusion stands solely on the market being some random place in Wuhan that is no more likely to form the early cluster.

He assigns this a 500x(!) factor, compared to our 2x. We specifically pointed to major mistakes in his calculation (covered above). In summary:

- His calculation assumes zoonosis will almost always start in markets, while in SARS1 it was 1 in 9, and in the USAID PREDICT project markets were given a low priority. This is a 5-10x mistake. (He tries to refute this using cherry-picked examples, which we address separately below).

- He then gives no weight at all (Zero!) to the conditions in HSM, implying an HSM vendor who interacts daily with many people in an unhygienic closed environment that was proven to form early clusters elsewhere, is no different from a random Wuhan resident. This is a 10-100x mistake, depending on how much more conducive you think HSM is. And even if you don’t think it is, just the fact it has 1000 people in the same space means it is more likely to be noticed, since there needs to be some critical mass of hospitalizations – how many people in Wuhan work in such a place?

- Even if you somehow manage to ignore this, there is still the alternative explanation of the Wuhan CDC moving just next door to the market during the outbreak, which could also easily account for 10-100x.

Since Scott’s odds are currently 17x zoonosis, fixing these mistakes easily turns him into an avid lab-leak supporter. So far, neither Scott nor anyone else has been able to provide any justification for these weird assumptions, and until anyone is able to do so, the lab leak hypothesis should be considered far likelier.

Until the zoonosis side is able to provide such justification, there is not much value in discussing the other evidence. Nevertheless, for good order, we’re attaching below the responses given by Rootclaim’s founder, Saar Wilf, to the claims in Scott’s second post (copied from the comments section there).

The CGGCGG expert

Scott says he “asked a synthetic biologist about [using CGGCGG] and he said:

“Nope. I would literally never do this if I were designing a small insert (maybe I wouldn’t notice if it happened by chance with ~1 in 25 odds in a naive codon optimization algorithm as part of a larger sequence). High GC% is bad. Tandem repeat is worse. Several other perfectly fine arginine codons. And I wouldn’t engineer a viral genome using human codon usage. An engineer would not do it.”

The opinion of a single expert in a private conversation is not a good argument. Examples of good arguments:

- Pfizer and Moderna vaccines recorded almost all arginines into CGG.

- Shibo Jiang inserted a furin cleavage site and used CGG for the leading arginine.

- If indeed the FCS was part of investigating the PAA -> PRRA hypothesis (see above), then PAA is already CG-rich (CCT GCA GCG) so virologists modeling how PAA could naturally evolve into an FCS could have decided to keep it CG-rich.

- Having a unique sequence can be helpful for easy tracking of mutations in the FCS during lab experiments.

Wet markets as transmission locations

“I think scientists had called wet markets as an especially dangerous potential transmission location in advance.”, and Scott follows up with quotes warning against markets.

These seem like the result of a targeted search for such quotes, and therefore have no probabilistic weight as they provide no comparison to other spillover sources. We didn’t claim no one warned against markets, just that they were relatively low priority.

In our post above, we provide an unbiased search we conducted that clearly showed markets were just one of many high-risk interfaces (search “USAID”), and a relatively low-priority one. Nevertheless, this was a quick search, and we are open to see it improved, but only using proper methodologies. Cherry-picking is one of the most basic human reasoning biases, and probably the most common way people get convinced of wrong things.

COVID’s ancestor

“No BANAL-52 relative close enough to create COVID from has ever been discovered.”